TEXT

In the last episode, I addressed the question of whether or not it’s a good idea to learn multiple instruments, or multiple styles on a given instrument like clawhammer and fingerstyle on the banjo, for example. And in that episode, I outlined the evidence indicating that not only does learning multiple styles or instruments not undermine your progress on other styles and instruments, but actually seems to enhance it. The impact is synergistic.

So from the standpoint of musical development, you can make a very compelling argument that you’ll develop further and farther learning multiple instruments than you would learning just one or learning multiple styles. Which is great, but in my view, there’s an even greater reason for doing so – that a life of continuous musical learning could literally save your brain and fundamentally and profoundly alter the trajectory of your life for the better, which is the topic of this episode.

So while this episode may not be directly about music, if you are a musician, then this is perhaps the single most important Brainjo Bite for you to watch. It’ll also be a great one to share with any non-musicians in your life, especially if there was anyone who gives you grief about your musical hobby or passion.

Also, if there is anyone in your life who you know is interested in maintaining cognitive function as they get older or staying mentally sharp and preventing Alzheimer’s disease, or who you think would just benefit from adding more music into their lives, I would greatly appreciate it if you share this episode with them.

Some of you watching may know that, in addition to being a musician, I have a background in cognitive neuroscience – the neuroscience of human cognition, things like memory, language and learning. And many years ago, I decided to direct that interest into training to become a neurologist, a doctor who specializes in the diagnosis and treatment of cognitive disorders among other things.

As you may know, this is a big issue. The typical adult will begin to see a decline in their cognitive function in midlife, and this can progress to cognitive impairment and in many, it will then progress to the most common form of Alzheimer’s dementia. Alzheimer’s is also quite common. Right now, if you are a man age 45, your lifetime risk of developing Alzheimer’s is one in 10. If you’re a woman age 45, that lifetime risk is one in five. Furthermore, the vast majority of people will experience a decline in their mental faculties as they get older, regardless of whether that progresses to the point that it’s severe enough to merit a diagnosis of dementia.

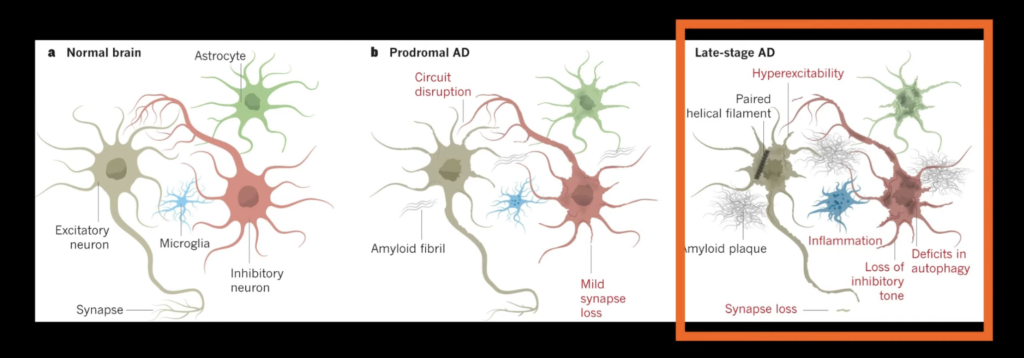

For many of us, losing our cognitive function and mental faculties as we age, especially memory, is one of our greatest fears, in many cases because we’ve had the experience of watching a loved one go through it. And it’s important to note that these things – cognitive decline and dementia – are a result of physical deterioration and degeneration in the brain. So the brain shrinks, gets smaller and microscopically we see things in neurons that shouldn’t be there, and those things are likely partly responsible for why the brain is shrinking.

So if we want to avoid these kinds of problems and stay mentally sharp as we age, then we want to prevent that deterioration in the brain from happening, which is what this episode is all about. And the good news is that there is much that we can do to reduce our risk of this happening.

As I said, I decided to pursue a career in this field years ago because I thought we were on the cusp of a breakthrough in the treatment of these conditions. At the turn of the 20th century, we thought that breakthrough would come in the form of a drug of some kind.

And I was involved in multiple clinical trials that tested what we thought were very promising treatments. None of those ended up being the breakthroughs that we were hoping for. And the chances that we’ll ever have a breakthrough in the form of a drug now seems vanishingly small, not only because of that lousy track record, but also because of what we now know about the nature of these conditions and about Alzheimer’s disease itself.

But that is not where the story ends, because at the same time as we were having one failed drug trial after another, a new body of research began to emerge that both demonstrated why the drugs were failing, and it pointed the way towards the solution that we were looking for. Research that shows that not only can we help protect our brain from decline, we can actually restore it back to a more youthful state.

There’s a popular misconception that our brain is in this unstoppable and irreversible state of decline because of the “aging process”. But that is not at all true. Our brain is in constant flux, and what we call aging is a dynamic and bidirectional process. It is neither unstoppable nor irreversible.

Much of the deterioration in the brain that we do commonly see is a product of lifestyle. And right now, the typical lifestyle makes deterioration with age the most likely scenario. But again, that is not inevitable. And the same things that we can do to reduce our risk of cognitive decline and dementia are also the same things we can do to boost cognitive function and mental wellbeing right here and now. That’s because the healthier our brain, the better we feel, the better we think, and the less likely we are to experience problems as we get older.

I imagine most of you know that there is research out there showing that exercising your brain is good for it, just like physical exercise is good for your body. It boosts cognitive function and it reduces the likelihood of cognitive decline and dementia. It turns out this hasn’t really been known for very long. It was the publication of the Nun Study in 1996 in the Journal of the American Medical Association that really kicked off this area of research.

In that particular study, a group of 678 Catholic sisters who were members of the School Sisters of Notre Dame were tracked over many years. And the purpose of doing so was to examine the relationship between various factors and long-term cognitive and neurological health.

The first headline-making finding that was published from this study was that features of their writing in early adulthood were significantly correlated with their risk of Alzheimer’s later in life. Specifically, it was the idea density of their writing in early life that was highly correlated with the likelihood of them being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s later in life.

And since then, there has been a great deal more research published that supports this effect of cognitive activity on brain health. Here’s a graph from a review paper looking at various health and lifestyle factors that have been studied in terms of their relationship to the risk of dementia. And of all those factors looked at in terms of their association with the risk of dementia, a cognitively active lifestyle was associated with the lowest risk of all.

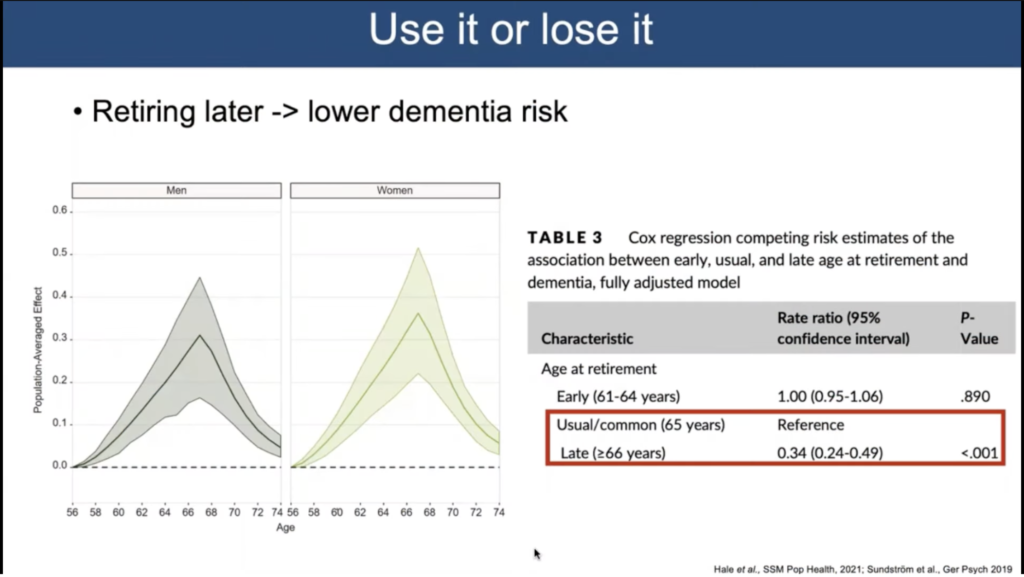

On a related note, retirement is associated with a significant worsening of cognitive function and with an increase in the risk of dementia. This graphic here is from a study in 2021 showing that those who retired later in life in their late 60s were 66% less likely to develop dementia than those who retired in their early 60s. And this was after correcting for other potentially confounding health factors that might lead someone to retire early.

Based on what we now know, this detrimental effect of retirement is very likely due, at least in large part, to the reduction in cognitive challenge that happens after people retire. For many people these days, their job is the main thing in their lives that provides at least some degree of mental stimulation. And that’s important because this particular effect of retirement leading to an increased risk of dementia is only likely occurring if retirement is leading to a less cognitively challenging life, and that need not be the case at all.

I know many of the retirees who are subscribers to Brainjo are quite cognitively active and who are almost certainly providing their brain with significantly more stimulation in their retired years than they were when working, and probably having way more fun doing so! So there’s nothing magical about retirement or working, but there is indeed something magical about regularly engaging in activities that are cognitively stimulating or cognitively challenging.

Demand Coupling Drives Degeneration

So what’s actually happening here? What’s accounting for this effect of cognitively challenging activities on the risk of cognitive decline and dementia?

Well, when you look at all of the science in this area, I think there’s a clear takeaway. In simplest terms, that is that the health and function of our brain is driven by the demands that we place upon it. And this is a phenomenon that my colleague and I in a recent paper refer to as “demand coupling.”

During the first couple of decades of our lives, the demands that we place on our brain are enormous. During that time, we are literally building the most intelligent system in the known universe – the human brain – from scratch. That includes building all of our highly advanced perceptual systems like vision, hearing, touch and proprioception that we need in order to extract high level information from our primary senses. And at the same time, we’re developing our core human cognitive capabilities, walking, talking, and socializing.

As a result, during this period of time in early life, our brain is receiving constant stimulation across the cerebral cortex in both hemispheres, day in and day out. And it is our brain’s adaptation to that stimulus that not only it enhances its capabilities as the brain matures, but also that keeps it in this healthy, pristine condition. And that’s not including all of the other things we tend to do mainly early in life, like getting an education and learning new sports, learning a musical instrument, et cetera.

What all that means is that for the typical human these days, the average amount of cognitive stimulation that the brain receives falls off a cliff after early life. And because of this phenomenon of demand coupling where cognitive challenge or demands are tightly coupled to the health and function of brain tissue, that causes a progressive deterioration in the health and function of the brain, which is experienced as cognitive decline, typically starting in the fourth or fifth decades, and then oftentimes progressing to the point of dementia.

And all of the drugs and supplements and nutrients in the world aren’t going to help grow and restore the brain if the stimulation isn’t there, if there isn’t anything for the brain to be adapting to. Just like you can eat all the protein and take all the creatine you want, and your muscles aren’t going to grow unless you’re also creating the demand for growth by challenging your muscles with resistance exercise, the same is true of the brain.

What Activities Build Better Brains?

All right, so if cognitive activity can help promote a healthier brain, boost our cognitive function and mental wellbeing and reduce our risk of cognitive decline and dementia, then what sorts of activities are best? Well, again, the best model that we have for answering that question is the cognitive and learning environment of childhood.

The ideal activities then are those that recreate the kind of whole brain workouts that we got every day as children, ones that stimulate plastic reorganization in all areas of the cerebral cortex on both sides.

What sorts of activities fit that description best?

Well, you could probably guess what I might say. Of course, music is one of them. In fact, I don’t think there’s anything better at recreating the kind of cognitive challenge that we received in early life. And you could add dance to that as well, as dance also provides a kind of cognitive challenge, very similar to music and not coincidentally, those things often go hand in hand.

So learning a musical instrument provides the perceptual, conceptual and motor challenges that characterize a whole brain workout and that replicate the kind of cognitive challenge that we received as a matter of course, in our early lives.

Things like crossword puzzles and brain games are great, but they’re more akin to isolation exercises than whole brain workouts, as they target very specific or isolated areas of cognitive function. They tend to leave out our motor system entirely, yet an enormous part of our cortex and our cognition is devoted to the planning and execution of movement. In many ways, the main job of our cognition and of our cortex is to plan and execute our next move in the world.

Music and dance exist in every human society ever known. And why might that be? I would argue because music and dance are the ultimate brain food. Every human loves it so much because it’s so good for our brains.

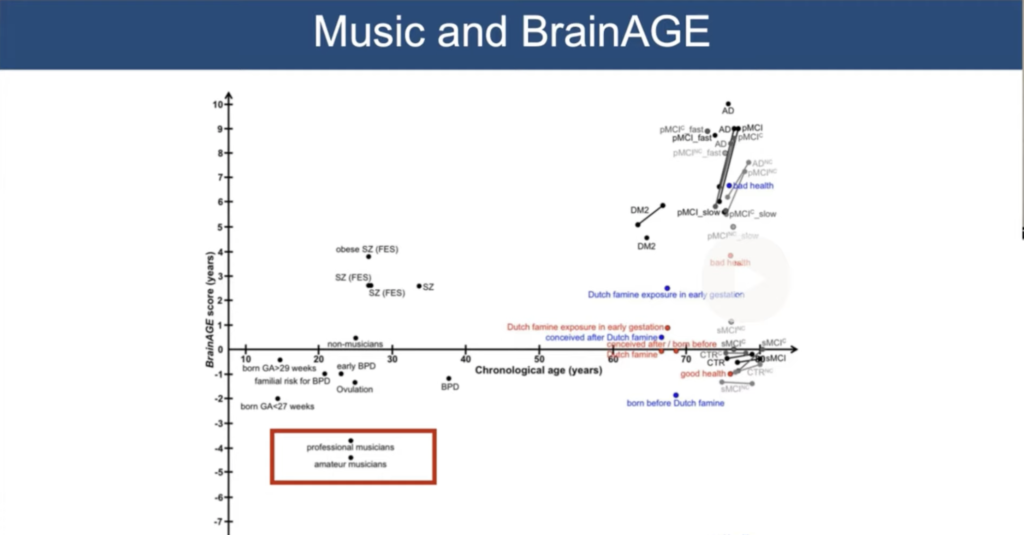

Here’s another study where they looked at the brains of subjects with a fancy MRI scan and used an algorithm to determine how old their brain looked just based on the MRI image itself. And then they compared the brain age that’s predicted by the MRI to their actual age and looked at all the various health and lifestyle factors that were associated with a brain that looked older than it should, and a brain that looked younger than it should. And of all of the things studied here, the people with the most youthful looking brains were musicians.

Why Multiple Instruments?

Now, back to our original question of learning multiple styles of music and multiple instruments. I’ve outlined the case for learning music to protect the brain and boost cognitive function, thanks to the fact that it provides this ideal whole brain workout that we need. But what’s the argument for multiple instruments and styles? Why not just stick with one?

Well, one of the most wonderful things about the human brain is that it can not only acquire, but automate new knowledge and skills throughout our life. By that I mean that most of what we know and most of what we can do is controlled by neural circuits that no longer require our conscious attention.

And that’s important because our conscious mind is a bottleneck. Because of that bottleneck, without being able to embed knowledge and skills into neural circuits that exist beneath conscious awareness, we would never be able to compound knowledge and skills. We would never be able to learn things like learn language, learn to walk, or learn a musical instrument.

On the one hand, this is fantastic. This compounding of knowledge and skills through automaticity allows us to continue to add new cognitive capabilities as long as we live.

But if we look at this through the lens of cognitive stimulation and cognitive challenge, it also means that an activity that was once extremely challenging and required all of our conscious attention and was super demanding on the brain becomes less and less so over time as we get better at it.

So when we’re kids, we’re developing all of the core cognitive capabilities that make us human, and everything is new and is being built from scratch. But by the time we’re adults, all of those core capabilities have been automated, which is a big reason why the typical cognitive demands of adulthood tends to be so much lower than those of childhood.

This is very similar to the body’s response to lifting weights. Let’s say you’re just starting out and you can only squat a hundred pounds, and it’s really hard. You can only do a few repetitions. Well, the longer you work out, the easier and easier that gets. And if you progress to being able to squat 200 or 300 pounds, that 100 pound barbell is no longer providing anywhere near the level of challenge that it once did.

So because we are so adaptable, the things that are challenging to us are always changing. And our brain happens to be the most adaptable organ by far, which means that in order to maintain the level of stimulation needed to keep it healthy and youthful, we need to continue to be learning new things that challenge the whole brain. And the demands placed on the brain are much greater in the beginning of learning an instrument or learning a new style than they are later on.

Let’s revisit this study I mentioned a minute ago, and we see that amongst musicians, the brains of amateur musicians actually looked a bit younger than those of professional musicians. Which is what we would predict based on what I’ve just described. Music is more challenging for an amateur than a professional, and so they will be reaping greater brain benefits from it.

So this is why if you’re looking from the perspective of brain benefits, it’s great to be a beginner at something because the more you have to learn, the more your brain has to change and grow, which means the greater the benefits it’ll be to its health.

Now, ultimately, new learning of any kind is fantastic. And one of the great things about music is that the possibilities for new learning are endless. Every new song is another opportunity. Every new chord shape you learn or picking pattern on the guitar or banjo or new accompaniment pattern on the piano. The opportunities for new learning are endless, and they’re also incredibly fun and rewarding.

But this also means that learning new styles or genres or instruments provides the greatest benefits from the perspective of your brain. And the worse you are at something, the more you stink, the better off you are. And that also means that if you’ve never touched an instrument in your life, your brain is going to benefit from learning one the most.

As I said earlier, I decided to pursue a career in neurology years ago because I thought we were on the cusp of finding a drug that would cure Alzheimer’s dementia, as did most everyone else in the field. That hasn’t happened, but the wonderful thing here is that in the intervening period, it’s become clear that we have what we need. The solution just looks very different than what we thought it was going to look like.

As you now know, one of the essential ingredients in that solution are regular, challenging whole brain workouts. But it’s equally important to make sure that the brain has the resources it needs to respond and adapt to those workouts – things like sleep, nutrition, and physical activity. That’s beyond the scope of this discussion, but it will be part of the Better Brain Fitness course that is now starting for premium subscribers to The Brainjo Academy.